The science of pro cycling race numbers

Here I am, once again trying to explain the arcane logic of race numbers, and the internet is surprisingly unhelpful, offering up only one or two insufficient links before trying to help me print my own race number, pin my own race number, or sign up for triathlons. (NOPE.)

Be the change you want to see in the world, etc. etc. Here we go.

The basics ⚭

All race numbers are grouped by teams. At any given race, the #1 bib (dossard, if you’re feeling French) goes to the defending champion, or to the new team leader of the winning team, if the defending champion is not on the startlist. Their teammates receive bibs #2–#8 in ascending alphabetical order.

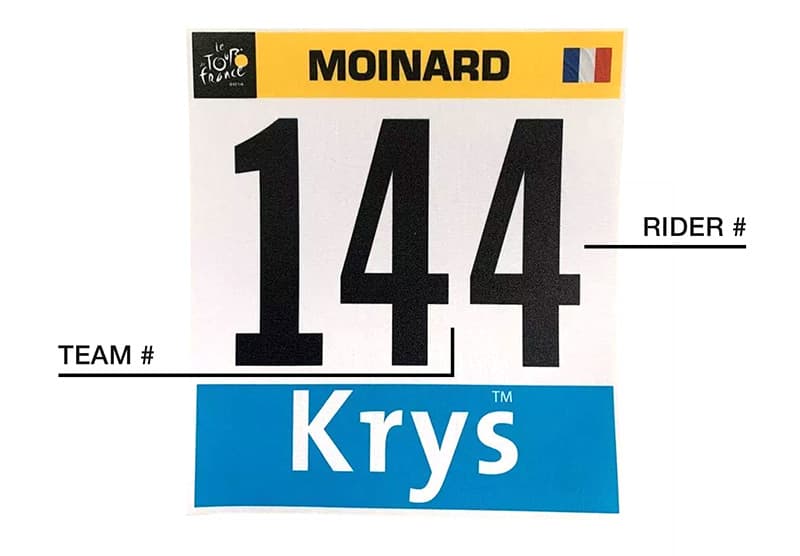

For the remaining teams, the first 1-2 digits is the team number, and the last digit is the rider number. The team leader of the next team is #11, with their teammates #12–#18. Then #21, with teammates #22–#28, followed by #31, and so forth.

The team order is assigned either alphabetically—the Giro d’Italia, among others—or by World Tour ranking—the Vuelta a España, among others. The Tour de France assigns the second and third slots to the previous year’s runners-up, and then the rest of the teams typically follow based on WT rank.

What this means ⚭

Once you know what to look for, there is a logic to the madness, and it makes it fairly easy to tell at a glance who’s who within any given race.

Many races will group their World Tour and Pro teams alphabetically, then group the continental or national (wildcard) teams below them. Races sorted by ranking will typically have the continental or national teams near the bottom also, as those teams have smaller budgets, qualify for fewer races, and have fewer riders who can win at the World Tour level.

Higher team numbers don’t necessarily indicate a lower ranked team, depending on the classification of the race and the number of teams participating. In the 2024 season, for example, an alphabetical startlist could place UAE or Visma in the 16th or 17th slot, despite being the two highest ranked teams in the World Tour. But as a general rule, the higher the number, the lower the team is ranked. The 18th slot onwards are typically the wildcards, i.e. continental and national teams, in first category races.

What the category? ⚭

Just when you thought it couldn’t get more complicated! Each race on the calendar is classified on a scale depending on the type of race and the prestige or difficulty of the parcours. This effects which teams participate and the quality of the startlist, which in turn effects what information the bib numbers offer at a glance.

At a first category race, all 18 World Tour teams are required to be present, and pro teams need a wildcard invitation to participate (2–4 wildcards per race). A pro-level race will have fewer World Tour teams, so more Pro, continental, and national teams are present. At a second category race, only a few World Tour teams may participate, and the majority of the startlist is continental, national, and development teams.

Knowing the category of the race lets you tell (roughly) how many World Tour teams there are, and thus at which point the team numbers starting indicating lower-level teams.

Crunching the numbers! ⚭

Here’s a real world example, comparing a first category stage race with a second category stage race, the Tour de Suisse vs. the Tour of Austria.

First category race ⚭

The Tour de Suisse is classified 2.UWT: the 2 indicates it’s race with multiple stages, and UWT = UCI World Tour, which means all WT teams have mandatory participation. Due to its place on the calendar, early June, it’s also used as a prep race for the Tour de France in July. This attracts a high-quality startlist.

Let’s look at the 2024 edition. Mattias Skjelmose from Lidl-Trek (formerly Trek-Segafredo) won in 2023, so he and his team get top slot. From there it’s the World Tour teams (WT) in alphabetical order, followed by the Pro teams (PRT) in alphabetical order, followed by the lone Swiss Cycling national team (NAT), which gets an invitation to participate in their home race.

Note that Team Visma and UAE are down there in the 16th and 17th slots, despite, as I said before, being the two highest ranked teams in 2024. That’s their luck of the alphabetical draw in a startlist of this quality, since neither of them won the previous edition. However, any team in the 18th slot and below indicates their lower ranking.

So in a first category race like Tour de Suisse, glancing at a dossard with #224 tells me it’s a domestique or stage hunter of a continental team, with a very long shot at reaching a podium. By contrast, a race number of #171 (Adam Yates, UAE Team Emirates), #101 (Egan Bernal, Ineos Grenadiers), or #1 (Skjelmose, Lidl-Trek) tells me they’re top contenders for the podium. And indeed, Yates won two stages and the overall GC, with the others finishing within the top 5.

Second category race ⚭

Now, let’s compare with the 2024 Tour of Austria startlist. It’s a second category stage race (2.1), so there is no mandatory participation for WT teams. It’s grouped in the same order as Tour de Suisse, which is handy for comparison purposes—World Tour teams (WT) in alphabetical order, followed by the pro continental teams (PRT) and then continental teams (CT) in alphabetical order.

Crunching these numbers gives us a much different story. The race takes place in July, which puts it in direct competition with the Tour de France, the most prestigious race on the calendar. Only four WT teams and two Pro teams are present, and without their star riders. The bulk of the startlist is all continental or development teams.

Diego Ulissi, the eventual winner, has bib #37—his team, UAE, alphabetically gets the fourth slot out of the four WT teams. (Remember, the 4th team = #3 on the bib, since the first team gets single digits, and effectively no “team number.”) Felix Großschartner is the UAE team leader (#31), by virtue of his being a solid (second-tier) GC rider, but also by virtue of his being Austrian (see Who’s #1? below). His teammate Ulissi is the better climber though, and comes away with the win on stage 3 and the lead of the race. As expected, the top five finishers are all WT teams, and their race numbers reflect that—Rivera (#5) and Sheffield (#6) from Ineos, the aforementioned Großschartner (#31), and Xandro Meurisse (lucky number #13, more on that below too) from Alpecin-Deceuninck. Two continental teams crack the top 10—Márton Dina (#122) in 9th place, and Ric Zoidl (#81) in 10th—which reflects the (lack of) quality in the startlist.

So the race numbers still tell us a lot, once adjusted for the race classification. It’s why I can pick up a cycling romance (*cough,* Spokes) and balk when the star rider is #141 at a 2.1 race. The author is trying to tell me he’s one of the best cyclists in the world—the numbers are telling me he’s racing on a continental team at an unprestigious race.

It’s worth noting that there’s another reason why you don’t often see the big names competing in second category races. Continental or development teams are working their way up through the ranks, their riders are often less skilled, the route is less optimal for racing, and the organizers lack the budget to provide full safety measures. Crashes are nearly 100% guaranteed, and the risk of race-ending or season-ending injuries is arguably higher than usual. Or, tragically, life-ending: this year’s final stage of the Tour of Austria was not contested after the fatal crash of André Drege (#171) on stage 4.

Who’s #1? ⚭

Who gets designated the #1 slot on a team depends on the type of team and the race. For one-day classics, the best classics specialist will get top billing. At a stage race, GC teams (those competing for the General Classification) will give their best GC rider the leadership role. For sprint teams, their top sprinter gets the spot. For stage-hunting teams—those who can’t compete in GC or bunch sprints—you’ll often see their highest ranked rider as team leader, or their best rider of the same nationality as either the race or the team.

For example, back when we were looking at the Tour of Austria startlist, six team leaders were Austrian, including Großschartner (#31) on UAE. As I mentioned, Großschartner doesn’t necessarily outrank Ulissi, but Ulissi is Italian, and thus at an Austrian race, they give the homeboy top billing.

At World Tour races, this pretty effectively sorts the riders, and often (but not always!) you’ll see lots of #1’s winning bunch sprints or on the final podiums, because the domestiques are doing their domestique things.1

At second category races, it’s more of a mixed bag of hopefuls coupled with national affection, so often (but not always!) you’ll see more non-#1’s coming out on top.

Exceptions to the rules ⚭

Have you noticed how many times I’ve said the word “typically”? Because remember, this is an arcane and endearingly random science, and there are ALWAYS exceptions. Let’s Q&A!

Q: What’s up with #13?

A: Cyclists (who are not

Sean Kelly) are often superstitious buggers, and the UCI, bless their hearts, are adorable enablers. Any other tampering with race numbers brings a swift fine to the rider and/or team, but the lucky (unlucky?) #13’s are allowed to break the rules and pin their number upside down.

Occasionally, they’re even allowed to dodge the number altogether. In the 2023 TDF, for example, Großschartner was on domestique duty for team leader Tadej Pogačar, which put him at #13. He chose not to wear the number at all and was assigned #14 instead, bumping the rest of the team down until Adam Yates pinned on #19, the “9th” rider for an 8-man team. Which brings me to…

Q: Why are some riders out of order?

A: At this point, honestly, who the fuck knows. It can be superstition, as mentioned above. Some riders have multiple surnames, and depending on where they’re racing, that country might order alphabetically based on different names. (IIRC, this happens more often in Spain, or to Spanish riders.) And I believe a last minute replacement can just slot in for the rider they’re replacing… I’ve never gotten confirmation this happens, but it’s appears to now and then.

Q: Why are some teams out of order?

A: If they look out of order, first off, make sure you’re not looking for an alphabetical listing when they’re ordered by rank, or vice versa. Another common thing is that the official registered name is what gets alphabetically sorted, so yes, Team Visma Lease-a-Bike gets ordered by “T” not “V”, or Bora-Hansgrohe gets bumped down the order when Redbull comes on as title sponsor, and it’s now Redbull-Bora-Hansgrohe.

Also, the Tour de France will occasionally slot their best French team just after the previous year’s podium; in 2023, #31 was awarded to David Gaudu and FDJ after he finished 4th in the 2022 TDF.

Q: Why is a superstar on a continental team?

A: It can happen, when a rider is working their way up or down the ranks. For example, Mathieu van der Poel, currently the 4th ranked rider in the world, was on the Corendon-Circus continental team and then the Alpecin-Fenix pro team before they got a World Tour license. He started off as a cyclocross star, and Corendon-Circus is predominantly a cyclocross team. Once he began racing on the road, the team got invited to bigger races due to the star power of MVDP. Same once Alpecin-Fenix (now Alpecin-Deceuninck) formed around him. His status elevated the team and scored frequent invites to prestigious races until the team achieved World Tour status.

A more common occurrence is when a superstar is at the end of their career. They can still bank on their fame, but don’t have the results to match, so they wind up on a lower ranked team before retirement. Think Peter Sagan to Direct Energie or Chris Froome to Israel Premier Tech.

Q: This top-tier sprinter doesn’t have bib #1, is that an insult?

A: Nah. They’re probably lucky (or unlucky) enough to be on GC team with a huge budget, so the GC leader gets the honor. Think Mark Cavendish riding for Team Sky during their dominant Wiggins-Froome years.

Q: This top-tier GC contender doesn’t have bib #1, is that an insult?

A: Nah. It can mean there’s dual leadership on the team or that the team has multiple contenders (see the footnote below re: the Roglič/Vingegaard/Kuss extravaganza). GC contenders will also fill a super-domestique role for other GC contenders on the team. For example, if a rider targets the Giro as team leader, he may be super-domestique while another teammate targets the Tour (and gets to be first in line if crashes or illness befall the chosen one). The high-budget superteams attract the top-tier talent, so they’re often stacked deep, with negotiations and politics going on throughout the year to keep the peace.

Q: Do the race numbers affect the order of the time trials?

A: In absolutely no conceivable way, other than a general trend of indicating the higher ranked teams. *Side-eyes PD Singer again*

In a prologue time trial, each team receives x number of time slots spaced throughout the day. (Riders from the same team cannot depart back-to-back, as this could allow drafting and shenanigans; also, there are not enough team cars to go around.) Barring bad weather, the best riders (i.e. GC riders or time trial specialists) usually get the final slots. That means lower numbers (better ranked teams and team leaders) are often weighted to the end, and higher numbers (worse ranked teams and domestiques) toward the beginning. It doesn’t makes sense (*cough,* Spokes) to say an Olympic time trial champion is #199. (flails and facepalms)

Once a stage race is underway, a mid-race time trial will have the riders depart in reverse order of the general classification, giving the rider(s) in the lead the advantage of racing last. So again, lots of #1’s toward the end, but only because the top-level riders have clustered around the top of the classification by this point.

Q: My brain hurts. Is there going to be a pop quiz?

A: I would never! Go take a Motrin and lie down in a dark room.

Q: I’m writing a cycling novel, can I hire you to consult?

A: Absolutely! Call me, babes. 😘

Hey! A recent and notable exception to this: Sepp Kuss winning the 2023 Vuelta. Kuss pinned on bib #24 as super-domestique for (then) Team Jumbo-Visma. Primož Roglič (#21) was ostensibly their team leader, with Jonas Vingegaard (#28) there to see what he could do, fresh off his Tour de France win. The team “let the road decide” who would come out on top, but before Roglič or Vingegaard could land a blow, a lucky breakaway on stage 6 put Kuss in the leader’s jersey. It’s considered bad form for teammates to attack each other (although Roglič and Vingegaard really, really, really wanted to), and so the team happily (according to some sources) or begrudgingly (according to others) rallied around their domestique for the win. This ended in the historic and unlikely result of a single team sweeping the podium, with neither the team leader nor GC favorite on the top step. ↩︎