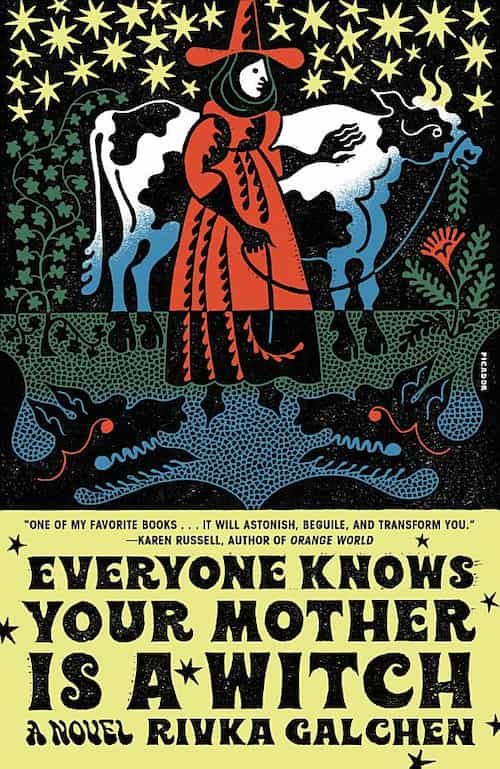

Historical (fan)fiction of Katarina Kepler, Johannes Kepler’s mother, famously tried as a witch. It’s fantastic, the character work, the structure, the narrative voice(s), the exuberant black humor that becomes blacker and blacker as it follows the warp of history. An impressive example of what the genre can do, no boring litfic pretentiousness here.

Note: the Keplers make me think of Susan Griffin’s seminal book Woman and Nature, where the timeline of major historical achievements is interspersed with the timeline of infamous witch trials to chilling effect. And also Ada Palmer’s Inventing the Renaissance, which shows that despite all our myths to the contrary, the “medieval” and “modern” overlap to a sobering degree, to the point of often being indistinguishable.

Pull Quotes ⚭

I try my best to like people. To expect good from them. If you see someone as a monster, it is as good as attaching a real horn to them and poking them with a hot metal poker. I really do think so. In order to avoid turning people into monsters by suspecting them of being monsters, I do my best to keep myself mostly to myself.

They have so much energy, Ursula’s people. It’s like going up against a thunderstorm. I have work to do, I have other obligations, whereas they—this is their work. They’re the guild of rumormongers. The society of theft-by-accusation.

Anyone who takes gentle care of a cow is someone I trust. It’s a more telling characteristic of a person than taking Communion. Certainly more telling than good teeth. Every cow has a secret name that you can discover if you spend enough time with the creature, if you present yourself as open to learning the secret name. There are a number of methods. The one I use I came across by chance as a child, when I was regularly the first person to the animals in the morning, bringing them branches and feed.

I had loved babies as a child, more than most people do, even. I loved their small fingernails. I loved the way they seemed to arrive older than their parents. I loved the courage they had to sleep as if there were no wolves, no soldiers.

I am astonished at all the expense and effort given to the useless work of books. Each party forbids the books of the other party. It’s a vanity. Hans tells me his books can be bought even in Rome, he says it proudly, and, sure, I see that. He also says the bookseller has to hide the books under the counter and offer them only to those who know to ask—the books are mistresses. The men brag about them. Another realm for snobbery. And recklessness. I suspect the only thing I would be interested in reading would be a history. But I’m told histories are hated, which is not surprising. People prefer to make it up themselves.

Hearts and alliances shift all the time, for reasons no better than the weather.

And that was that. I trusted him, because he told me that the seeds of the butterblume delphinium are the swiftest cure for lice, even as the same seeds fermented in honey water can be a poison if used too often on the gums, or for epilepsy. He saw delphinium as I saw delphinium. As a plant capable of good and evil both. As a plant that required the knowledge and good intentions of man.

I’m always polite to them, Greta. You’re right that we have to see the good in people, at least in people who have power over us and who will be angry if we see them in another way.

His defense poured over me like used cooking grease. He saw in Leonberg a horrible place.

That was my encounter with the author of The Harmony of the World.

“Is the argument clear? Is it compelling?”

“Well,” I said, “it reminds me of church.”

“What do you mean?”

I said that I meant that, for example, as a sermon, I thought it would go over very well. The audience would like it.

“Ah, I see.”